Gelukkig zie je ook dat sommige serieuze site toch ook weer juist heel lange stukken gaan maken en/of plaatsen. Zo geeft NRC elke week links naar meerdere, zeer lange en diepgravende artikelen, van her en der over het net. Ik heb zojuist de betreffende redactie de link gestuurd naar het navolgende stuk. Een stuk dat ik zelf ontdekte door een column van Mart Smeets (in/op NuSport(.nl), vanwaar akte. Mart schreef in zijn column dat het toch vreemd was dat dit stuk in Nederland zo weinig aandacht kreeg, terwijl het toch juist voor de Nederlandse Sportwereld een erg belangrijk verhaal is, hoe triest het in zichzelf ook is. Veel basketballers in Nederland hebben dit verhaal, of delen ervan, wel meegekregen, tenslotte zijn wij gezegend met de speelster Naomi Halman, zus van de twee hoofdpersonen in dit in- en intrieste verhaal: het verhaal dat de aanloop van de dood van Greg Halman, door de hand van zijn broer Jason, ontrafelt. Nu, in de dagen na de slachtpartij in Newton, past ook dit verhaal best: ofwel hoe moeilijk mensen het kunnen hebben die psychisch in de war zijn... (van ESPN.com)

17 days in November

Brothers Gregory and Jason Halman -- and the descent into death

Otto

Greule Jr/Getty ImagesGreg Halman played for the Seattle

Mariners during the 2010 and 2011 seasons.

Otto

Greule Jr/Getty ImagesGreg Halman played for the Seattle

Mariners during the 2010 and 2011 seasons.HAARLEM, The Netherlands -- Everything that would destroy them had already been set in motion when Gregory and Jason Halman squeezed into the narrow staircase that led to the tattoo parlor. They turned sideways to fit through the opening, their broad, muscular shoulders crowding the walls. Paolo Ponziani drew the design they described, then sat them down, one after another, to ink it in the place they requested. Even as he started to outline the cross and the initials G and J, the symbolism struck him. The location, a tattoo high between the shoulder blades. I've got your back. The cross, which was almost always in memoriam. Never before had he done a tattoo expressing such a close bond between people who were still alive. The needle hurt in the sensitive spot on the back of the neck, and the brothers howled. Jason, younger by 18 months, had a higher tolerance for pain. Paolo finished, and the brothers took turns in the mirror, making sure the tattoos were identical.

Gregory and Jason shook hands. "It's done," they said.

Paolo looked at the powerful teenagers and their fresh wounds. A promise, or perhaps a prayer, was written in cursive letters above and below the arms of the cross.

Brothers for Life.

November 4, 2011

Seventeen days before he killed his brother, Jason Halman drove him to a hotel near the Amsterdam train station. There'd been tension the past few days. Gregory Halman wanted Jason as his plus-one for the kickoff dinner of the European Big League Tour. They shared an apartment in Rotterdam, talked every day even when Gregory was in the States playing for the Seattle Mariners. They went everywhere together, even to this event a year earlier. Except, for the first time in their lives, Jason said no. Big league stars would be inside the hotel, men like Prince Fielder, Giancarlo Stanton and Adam Jones. They'd all look at him and think he was a failure.

Jason's refusal angered Gregory, who made up an excuse for the organizers. They'd just assumed the Halman brothers would be together. They rode side by side in the blue Lexus, filling up the seats, physically close but worlds apart. The brothers arrived at the Barbizon Palace hotel, an old sailor's chapel overlooking the canals and the station. A train disappeared behind the gilded façade every few minutes. Gregory stepped out of the car, alone. Jason merged into traffic, alone, turning right out of the hotel. He circled back on the road that led to the house where the Halman boys once shared a bedroom. Jason took out his phone and dialed his mother.

An inheritance

The brothers grew up in the long narrow room on the top floor of a row house in Haarlem, with a slanted ceiling and a view down into the street. Their hometown was near the water, west of Amsterdam. Inside their room, a little America took shape. A poster of Ken Griffey, Junior, hung on the wall. They tacked up pennants. Their older sister, Naomi, desperately wanted the Florida Marlins one. The pretty aqua color caught her eye. Her brothers wouldn't budge. "You don't love this game like we do," they said. The shared space was a shrine to their dreams.

AP Photo/Rob JelsmaJason Halman was an amateur player with the Corendon Kinheim club in Haarlem.

The boys inherited baseball from their father. Eddy Halman played in Aruba, then semi-professionally in the Netherlands. With thick corded forearms and a wide muscular back, he'd drive home runs on top of the old world houses across the canal from the Kinheim club's stadium. He married a talented softball player, Hanny Suidgeest, and they had four kids in about as many years. The middle two were boys. When Gregory was only twice the size of his father's big hands, he could grip a miniature Louisville Slugger. Once someone snapped a picture -- Gregory tiny in Eddy's arms, the bat on his right shoulder.

The brothers heard tales of baseball in America. Eddy told them about his own failed dreams of playing there. The pennants stoked passion for mythic cities. Chicago. New York. Seattle. They studied Griffey's stance and how he wore his pants. They tried to imitate Barry Bonds and Chipper Jones. Eddy taught them, too. He threw pitches at the boys, drilling them in the back. If they cried, the game ended.

Gregory and Jason stored baseball cards in black binders. Naomi can picture clearly the two boys, with bright eyes and curly hair, Gregory's skin darker than Jason's, huddled in their room, talking about what their own baseball cards would look like one day. When Gregory was 7 or 8, his oval face already set in determination, a friend asked what he wanted to be when he grew up.

"A professional baseball player in America," he said, with certainty.

The friend laughed at him, told him Dutch boys couldn't play in the major leagues.

"Why?" Gregory answered. "My father was a former professional baseball player."

Gregory and Jason Halman wanted to be just like their dad.

November 4, 2011

Seventeen days before he killed his brother, Jason met his mother in the narrow one-way street outside the house where he grew up. While Gregory traded big league stories with a table of fellow baseball stars, Jason and Hanny could eat a quiet meal together.

"What do you want?" she asked.

"Rump steak with green beans and potatoes," he said.

This surprised, and pleased, her. He didn't confide much in her, or anyone really. He never wanted a home-cooked meal. Always takeout pizza or spare ribs. Only later did she realize he wanted her to feel happy. Since Hanny and Eddy divorced, there'd been tension in her relationship with Jason. What a wonderful surprise it was, then, to have her son back for a few hours.

Doug Benc/Getty ImagesGregory Halman played for the Dutch national team in 2009, representing the Netherlands at the World Baseball Classic that year.

The Halmans worried about Jason. Gregory seemed to carry a vague and un-expressed concern for his brother, detectable through odd phrases and body language whenever the subject of Jason would arise. A friend in America noticed this pattern and asked him about it; Gregory changed the subject. When Naomi was younger, and would go play basketball in other cities, she'd have nightmares that something had happened to Jason. "I think we all know that Jason wasn't as happy as he seemed," she said. Hanny worried about him, too, of course. His dreams hadn't come true. Jason kept his disappointments to himself. The only hints came when he'd take off his shirt, which he liked to do when he'd sit in the window of his apartment on sunny days. Tattoos covered his body. Two inked daggers jammed into his gut. One handle said "father." The other said "mother." On his chest, in a frame of barbed wire, were the words: "Feel the Pain." Ponziani had tried to talk him out of it. Jason insisted.

As Hanny cooked dinner, Jason started talking. The words poured out, moving from subject to subject, disorganized and jumbled, as if the speed and force of the thoughts overwhelmed the ability of his brain to organize them. Jason talked and talked and talked. Out of this first crack rushed a torrent of once-secret pain, like he'd cut an emotional artery.

Moving forward, pulled backward

The boys inherited more than baseball from their father.

When things went wrong, Eddy Halman saw the hidden hand of conspiracy. Politics and bad luck had robbed him of his chance to play in the States. Blame and denial came along with the powerful swing. "He's a difficult guy," said Jan Collins, a baseball coach who grew up with Eddy in Aruba. "When he takes booze, Eddy is a different guy."

Violence shadowed the Halmans' lives. Eddy did jail time for the most public of his attacks, breaking out windows in Hanny's house, jealous over Hanny dating a new man. He came to the stadium and did the same thing to the windows in her car. Then he climbed the bleachers looking for her. The police took him away. The boys saw. They learned. Some thugs assaulted Gregory in a nightclub bathroom, and he caught up with one of them a day or so later and broke the guy's jaw. "Trouble followed this family," a major league scout would say later. "There must be some kind of tragic temper gene."

Baseball worked as a translator between the things they felt inside and the world around them. Dampened anger. Gave self-esteem and joy. Their youth team moved fields after Gregory and Jason's home runs landed on an adjacent diamond while older division games were in progress. They outgrew a stadium. They outgrew their friends. Gregory looked like a man. Still, former teammate Tom Stuifbergen said, "Everybody thought Jason was better."

Gregory visited America when he was around 12. He walked out a concrete tunnel to the wide green of Yankee Stadium. He saw a game at Wrigley Field. In New York, he made his mom speak English to him on the subway. He wanted to feel like this was his home. When they returned to Holland, he brought a new Timberland backpack with him, and the bag went everywhere, carrying the idea of America along with his gear.

Gregory played with grown men in the Netherlands. They saw the ball soar off his bat and accused him of corking. He hit the same towering homers with their bats. He could run and throw, and he acted like it. He refused to shag balls. Sometimes he didn't hustle. He pouted when things went wrong. The trajectory of his talent struggled to escape the gravity of his inherited flaws.

Scouts for the Seattle Mariners took their seats one weekend in 2004. Gregory, 16, was MVP of the Dutch professional league. That year, he'd missed the Triple Crown by a percentage point. During batting practice, he blasted opposite-field home runs. The scouts called Seattle. Gregory Halman signed his minor league contract in a bowling alley across from the stadium. Jason knew his turn was next.

Gregory barely escaped Holland. Because of the earlier assault, he couldn't get in any more police trouble. One night, not long before he left for America, Gregory went to a party with Jason. A fight broke out and Gregory swung. The police arrived and detained him.

Jason realized what was happening.

He said he threw the punch.

November 5, 2011

Sixteen days before ambulance lights made their street glow blue, the Halman brothers rode together to the opening baseball camp of the European Big League Tour. Gregory slipped into an embrace of camera flashes and screaming kids. Jason disappeared into the crowd. There's no way to know why he chose to attend this event but couldn't find enough strength for the dinner. Whatever his private reasons, one thing seemed obvious: He was struggling.

AP Photo/Rob JelsmaJason, shown above in the background, struggled while his brother's baseball career took off.

Utrecht was the first of four camps, followed by Amsterdam, Prague and Parma, Italy. Holland is the baseball capital of Europe, with a thriving youth program. The national team had captured the world championship in Panama a few weeks earlier, and players from that team joined the big leaguers. In Utrecht, and then Amsterdam, kids surrounded Gregory Halman. When he talked about his life in America, the kids crowded into bleachers, all their eyes locked on his. The other big leaguers noticed how comfortable Gregory acted with the children. He seemed to understand something about being small.

"It's right there in front of you," he told them. "It's dreams. You got to have dreams."

Jason Halman stood alone on a balcony overlooking the indoor practice field. He wore a skullcap with sunglasses perched on his head, blue jeans and a black jacket. A silver railing and a mesh fence separated him from the world champion Dutch national team members, who wore their uniforms. Five months before, he'd been with them, preparing for Panama. Reminders of his own childhood dream surrounded him during these days, and as if to prove the universe had a nasty sense of humor, the parent of a recently signed boy asked Jason when he'd be getting a big league deal.

June 2008

His baseball career, once full of promise, had been marked by disappointment and rejection. Three years before he killed his brother, Jason traveled with his club team to a tournament in Italy, full of hidden anger. Late one night, he sat on the edge of his bed in a seaside town, backed by the ochre hilltops of Tuscany. Ninety miles separated him from the place where his dream fell apart, during that crushing summer of 2006. The bedside light chased the shadows of the hotel room.

He was 19 years old, stuck in neutral. Seven years earlier, he'd been all potential, finishing second in the Cal Ripken World Series home run derby in America, getting a hug and autograph from Ripken himself. All that had disappeared. He'd lost his spot on the national team and any realistic chance of signing with a big league club, his baseball life reduced to the same club team for which his father played. In a sense, his dream had come true. He'd grown up to be like Eddy.

A teammate stretched out in the other bed. Everything was still, until Jason's voice broke the silence. His teammate swung his legs around and sat up to listen.

Two years ago, that's when it happened. I went to the Major League Baseball camp in Italy. Gregory signed when he was 17. I was 17.

Jason searched for words.

They stole my dreams.

Jason told about a carnival in a nearby town. He and some teammates kicked a soccer ball around, accidentally ricocheting it off a ticket booth. Cops wanted identification, which Jason kept at the camp. They gave him a ride, where he produced it, settling the matter. Except the coaches singled him out. Blamed him for causing trouble. Sent him home. When he returned to Holland, the junior national coaches kicked him off that team, too. Nobody ever scouted him again.

Jason didn't tell his teammate everything. Some facts and details got lost in the construction of his defenses. In the hotel room, he struggled to remain calm. Keeping all this pain inside seemed of vital importance, and his roommate wondered why. Jason looked down at the floor when he showed weakness. When he raised his head and said, "F--- it," he tried to act tough again.

Head down.

My dream was stolen.

Head up.

F--- it.

Jason pushed away his pain and went to sleep. He kept chasing his dreams, playing for a club team, working to get recalled to the national team. A year before he killed his brother, he finally made it back. He played backup catcher and DH. After two years of waiting and hoping to get signed, he had enrolled in a university, studying economics, found an apartment in Rotterdam, made friends, built a life. The World Port Tournament loomed on the next year's calendar, held in his new home, and in October, the Dutch team would compete for the world championship in Panama. Jason called his mother and listed all the things going right in his life.

"I'm happy," he told her.

The Rotterdam tournament approached. On May 30, six months before he killed his brother, Jason and his teammates finished practice and took showers. One by one, they met with head coach Brian Farley. Twenty-eight players waited their turn. The roster limit was 24.

Jason sat down in the office. Farley told him they'd decided to go with two catchers and, though Jason was a better hitter, he struggled defensively. The coaches felt more comfortable taking a different second-stringer. Jason stood up and walked out of the room. He didn't shake Farley's hand. That night, he called his mother to tell her he'd been cut. He asked for a plane ticket.

"I want to go to Greg," he said.

November 6, 2011

Fifteen days before Gregory died, the new record by the rapper Drake leaked on the Internet. It was the night after the European Big League event in Utrecht, and the music quickly spread around the world, including to the front bedroom of the Rotterdam brownstone Jason Halman shared with his brother. The street led down to a wide avenue of pawn shops and Surinamese takeout. White framed windows, bright against the rust brick walls, opened during nice weather. This was where Jason liked to sit with his shirt off, showing his tattoos to anyone who walked past.

The daggers. Feel the Pain. Strangers saw what he wanted them to see. He ran with a tough crowd. The few times he'd visited Aruba, family members knew to watch close in case they needed to pull him out of a fight. "The last time he came, he was like, 'Don't you have nobody to beat up? I want to beat up somebody,'" a cousin on his father's side says. "I'm like, 'Are you crazy?'"

So his anticipation of this new record seemed odd. Most rappers brag. Drake's lyrics flinch with introspection and insecurity. He aims at himself. Instead of hiding pain, he revels in sharing it. Jason's life was an exercise in avoiding revelations. The first track, "Over My Dead Body," began with a sigh of piano and atmospheric electronics. Minor chords, moody. But Jason recognized something in Drake's lyrics. "Drake is like me," he told his friend Albert Landsmark. "Half-white, half-black."

What did Jason see in himself?

"Why am I the only one with these green eyes?" he once confided to a friend. "If I was a little more Greg's color, maybe people would love me more."

The new Drake tracks played over and over.

You hate being alone

You ain't the only one

You hate the fact that you bought the dream

And they sold you one

June 2007

Like his brother, Gregory's baseball career was stuck in neutral. Four years before he died, he dropped his Timberland bag on the floor of his rear corner bedroom in Everett, Wash. He'd been sent back to the Mariners' Class A club there. The double bed and blue cotton comforter were painfully familiar. He stared at his luggage. Opening the closet door was as far as he'd made it. His clothes stayed in the bags, which stayed on the floor.

Kathy Chapman, a surrogate mom to the ballplayers who lived in her house, came into the room. She sat near the door. Gregory sat on the bed, his head down. They'd met a year before. After playing 26 games in 2005 in rookie ball, Halman moved up to Everett in 2006. When he first moved in, Gregory's smile lit up a room, and Chapman's house soon filled with the pitter-patter of Dutch, and of kids watching baseball when they weren't playing it. But there was something else, too. He was his own worst enemy.

Otto Greule Jr/Getty ImagesGregory Halman wasn't drafted, but signed as a free agent with the Mariners in June 2004.

Everyone saw his talent. He couldn't hit a slider or a curve, and he struck out a lot, but that could be fixed. The real problem followed him from Holland. He stole risky and unnecessary bases to pad his stats. He got pulled from games for not running out ground balls. Sometimes he seemed most concerned with the best batting gloves. A Seattle official once told a competitor, "He is a coach away from being released. He needs his guardian angels."

On road trips, like one night in Boise, the radio crew would see him strolling out of the hotel a few minutes before curfew, headed for a night on the town. His second year ended after 28 games when he broke his hand punching someone during a bench-clearing brawl. After two years in the States, he'd hit eight homers and struck out 51 times. Still, potential won the day. Gregory hit for power, could run, throw, field. If he could hit a slider, he could be a five-tool star. A lot of people believed in his talent.

The Mariners promoted him to Class A Wisconsin for 2007.

Gregory lasted 52 games.

He found himself back in the 1,500-square-foot rambler in Everett, sitting in his new old bedroom with Kathy. "I can't believe this," he said. So his bags stayed on the floor. His clothes stayed in the bags. The closet door remained open.

He'd failed -- struck out an incredible 77 times, walked just three. His average was .182. That night, as he put off moving his stuff back into his closet, Kathy listened to him rage. He was pissed at baseball. At the world. Pitchers wouldn't throw him a cookie. That's what he called the pitch he liked. "They" threw him sliders and curves. How could they do this to him?

Kathy sat him down, and like so many people before, told him that his success depended on letting go of all the baggage he'd brought with him from Holland. She told him that he'd always been the star. Took things for granted. Now everyone had talent. "You've got a lot to learn," she told him, "You need to grow up."

"That's the same thing my mom said," he replied.

November 12, 2011

Janos Vajda/epa/CorbisThe Halman brothers' older sister, Naomi, starred for an Italian pro basketball team.

The last event of the tour took the big leaguers to Parma, which completed a circle for Gregory, who had nine days to live. On his first baseball road trip in what would become a life of them, he had traveled to Parma. He was 10. During the trip, he looked for the perfect gift for his mom. Coaches called her later to describe his diligence. Finally, he settled on a coffee mug.

This trip across Europe with the American stars did him good. They went out in Prague, and a smiling Gregory posted tourist pictures on Facebook. He'd never lost the joy he felt when he first looked into a Mariners locker and saw the uniform hanging there, his name on the back, the reward for growing up and leaving the weight of his past behind.

His sister Naomi lived up the road outside Bologna, where she starred for an Italian professional basketball team. When the tour ended, he planned on staying with her for a few days. A year had passed since they'd been together. Naomi, in addition to having a vicious post game, looked like a runway model. She carried the Halman smile, a searchlight of teeth. Even being around it, and her, for a few days would do him good, too. She began to pick restaurants and make plans.

But his phone kept ringing as he traveled from place to place. Jason said they needed to talk. Gregory canceled his visit with Naomi. Angry, she asked why. What could be so important?

"I need to see Jason," he said.

November 12, 2011

Nine days before he killed his brother, Jason began posting on Facebook.

He took his phone and retyped a lyric from the Drake album. The song "Look What You've Done" spoke to him, the reference to repeating the mistakes of the father, the song's open letter of thanks and apology to a patient, loving mother. Jason wrote: Just a young kid in a Lexus hoping I don't get arrested. Just a young kid going through life worried I won't be accepted.

Otto Greule Jr/Getty ImagesGregory Halman's path wasn't easy, at one point being sent down to Class A.

While Gregory walked in a room and made it his, Jason felt greeted with rejection. He saw it everywhere. Whites thought him black. Blacks, white. Baseball didn't want him. Gregory left him behind. For all his life, he'd seemed to imitate Eddy or Gregory. He walked like them, talked like them. If someone asked Jason to go to a movie, he wouldn't go unless his brother went. "He always felt like a copy," says Ponziani, the tattoo artist. "It was always pretty clear to me he wanted to emulate Greg. The biggest admiration for an older brother I've ever seen in my life. We all know people who've got brothers. I've got an older sister. Sure, I love her. But she's not my idol. Jason was exponential with that. He was talking a lot about the success of his brother."

Jason asked his friend, Albert Landsmark, to listen. Gregory leaving for Prague gave Jason time to think, and he knew for sure his baseball dreams were over, and where to place the blame. "His father f--- him up," Landsmark would say later. "He had a chance. He wanted to sign so bad."

This was one of the things he didn't tell his teammate in the Italian hotel room: Before the camp in Italy, the same year Gregory left for the States, the Mariners offered Jason a contract. Not much money, low enough that Eddy's refusal didn't surprise the scout. The summer held several important tournaments, and Eddy wanted a bigger offer. Gregory signed for six figures, a massive sum which Eddy spent like it was his. He figured on a second windfall from Jason. It seemed like a smart bet. Everyone, including the scout, figured Jason would play well during those events. He didn't. Clubs lost interest.

As Gregory traveled with the Big League Tour, to Prague and then Parma, Jason talked to anyone who would listen. He messaged Ponziani, telling him he wanted more tattoos. Until the past few days, that had been his only means of expression. Gregory's tats were aspirational. Reminders: "No Grind, No Shine." Celebrations: a baseball globe with the words "My World." The art on Jason's body hinted at unknown pain. An hourglass with the sand slipping away. Feel The Pain. His tattoos didn't deal with baseball. Actually, that's not entirely true. Just below the "Brothers for Life" image was the silhouette of a little boy, head down and walking away, about to let a bat slip from his hands.

Honesty felt good.

He told Albert that he'd been ready to die, but everything seemed different. Releasing the things he'd kept hidden removed a burden.

"He found a new Jason," Landsmark says, "and he was ready to live now."

Long apart, briefly together again

This was the clarity Jason had been seeking since he got cut from the national team. The distance between his own future and his brother's never seemed more unbridgeable than in the days following his meeting with Farley. Four days after that conversation, Gregory got called up to the Mariners, his second promotion in as many years. The club hoped he'd never go back down. So when Jason arrived in Seattle, he saw all the things he wanted but would never have. He'd long sensed the whispers, and now he'd saw it himself: "I'll always be the little brother who doesn't make it."

Eddy traveled with them, and Gregory paid for everything. Those days were magic. Gregory hit his first big league home run. Off a slider. Jason posted a joyful message on Facebook: "Homerun #1 is a fact bro, pops tearing up so proud of u dawg just like ur lil bro u daa mannn!!!"

Something else happened during that trip, something he didn't write about. At the ballpark, Jason put a wad of tobacco in his lip and spit into a cup. An usher told him to stop, but when she learned his brother was famous, she bent the rules. As he flew back to Holland, this ate at Jason, who'd never been further from the little boy flipping through baseball cards with his brother.

In Seattle, Gregory started hot, looking like he might be starting a long career, only to collapse, striking out over and over again: Curve balls and sliders. The Mariners sent him down to Triple-A and began finding new outfielders. Devastated, he returned to Holland. He refused to play winter ball. Some of his friends didn't even know he'd come back; usually, there'd have been a welcome-home bash. "F--- baseball," he said. The apartment vibrated with the matched pitch of two brothers in pain, both wounded by their unconditional love for a game. They didn't leave the apartment much, connected again as they'd been as children, this time not by the hope of a dream but by the pain of seeing that hope die. Brothers for life. "Two empty shells," Eddy said, "trying to motivate each other."

November 21, 2011

As Gregory Halman was dying, his girlfriend called Eddy. The paramedics worked in the house.

Eddy called Hanny.

"Jason stabbed Greg," he told her.

She couldn't speak.

"Did you hear me?" he yelled.

Silence.

"Did you hear me?"

Hanny picked up Eva, their youngest child, and drove toward Rotterdam. She phoned Naomi in Italy.

"What did he do?" Naomi asked. "What happened to Jason?"

"Jason stabbed Greg and the police are there," Hanny said.

Eva's phone rang. Eddy. Eva screamed. Naomi heard, and then she knew, too.

Jason

O. Watson/US PresswireGregory Halman struggled with his

hitting at times, unable to conquer sliders and curves.

Jason

O. Watson/US PresswireGregory Halman struggled with his

hitting at times, unable to conquer sliders and curves.November 13, 2011

Eight days before he died, Gregory walked down the wide, bright concourse of the Amsterdam airport, returning home from the Big League Tour. Jason parked outside arrivals, Landsmark riding with him. Gregory walked into the blast of cold air and found the blue Lexus. He looked inside.

"Something tells me you killed somebody," he said.

A mood descended like fog. A week of confusion poured out of Jason. "Easy, easy," Gregory said.

The ride took about an hour. In the car, and at home, as Landsmark would recount, Jason talked about the pain. About the pressure he felt being Gregory's brother, about the things he'd held inside, how Jason did everything for his brother, listened to him, counseled him, took in his pain, but Gregory wouldn't do the same for him. Both of them cried. Jason wanted Gregory to admit he understood the things happening inside of him. That he felt them, too.

"I know you got the pain like I got the pain," Jason told him.

Koen

van Weel/AFP/Getty ImagesMourners with red baseball caps

attend Gregory Halman's funeral on Nov. 29, 2011.

Koen

van Weel/AFP/Getty ImagesMourners with red baseball caps

attend Gregory Halman's funeral on Nov. 29, 2011.

A eulogy and an explanation

Five days after Gregory died, his uniform arrived from Seattle in a UPS box. The scout who had recognized his potential held it in his hands. Compressing so much into a few pounds of empty cloth made the loss more intense. The scout drove the package to Haarlem, looking in his rear view mirror every now and again, the box on his back seat. That's what was left of Gregory's dream, and he carried it back to the house with the Ken Griffey poster on the wall. Naomi dressed her brother, putting his uniform on for the last time, checking to make sure everything looked perfect.

Thousands came to the viewing. Gregory looked asleep, sunglasses on his head, his mouth slightly open, a stitch or two to close the wound. The program said Brothers for Life. The family requested mourners wear red hats. Jason always wore red hats.

The scouts from the bowling alley came. Some of Gregory's Mariners teammates flew over. They stood in the narrow bedroom at the front of the house. They looked out the windows of the white limousines and saw hundreds of mourners lining the roads, three and four deep, with many more already inside the chapel. They saw mourners receive little photos of Gregory; Hanny designed them as baseball cards, like the ones in the black binders.

Hanny walked to the front. She started her speech with her younger son. People who didn't know the family shifted a bit uncomfortably.

Jason died inside five years ago, she said. It happened at the camp in Italy. Jim Lefebvre, the field director, ended Jason's dreams with a threat as certain as a rattling anchor chain: "I will make sure that no club will ever sign you." That is what Jason had told Hanny three weeks earlier, on the night she realized something was wrong, and what Hanny told the thousand mourners.

"He was broken," she said.

Then she remembered Gregory. She told about his first baseball trip and how he'd searched for the perfect gift. She reached down and pulled out two glasses, both of them from Italy. The first was the coffee mug Gregory bought on that initial trip to Parma 14 years ago. The second Gregory bought for her on the Big League Tour, carrying it with him when he boarded the last flight of his life.

Layers upon layers

Jim Lefebvre says he never threatened to blackball Jason Halman from major league baseball. Even if he did say it, he doesn't have that kind of power. He choked back anger when he heard he'd been named in a eulogy. "That is false," he said. "That is absolutely false. That pisses me off."

Coaches remember Jason seeming disinterested during the camp -- and wondering why. Lazy, not hustling to block balls or sprint out grounders. The Italian cops claimed Jason threatened them. A friend who was there said Jason didn't. Maybe he got profiled; Italian cops are notoriously racist.

Mike McClellan, the head of MLB's European operation, offered Jason an opportunity to try out for a place at the camp the next year. Jason didn't show up. Near the end of the workout in Amsterdam, a local coach handed McClellan a phone. He answered it. Hanny tried to explain Jason's absence, offering excuses, and asked if he could have another chance. No, she was told, Jason needed to be present at the tryout. Maybe next time. Another year passed, and Major League Baseball returned to Amsterdam. Jason didn't show.

November 15, 2011

Many things came to the surface six days before Jason Halman killed his brother. He called his older sister.

"Why did you leave me behind?" he asked.

Gregory went to America. Naomi went to America, too, to play college basketball at UC Irvine. They had abandoned him. Jason told her he didn't want to be alone anymore.

Naomi's college career didn't last long, loneliness pushing her home. Gregory was mad but understood. Jason couldn't get over it. Was he upset she left him behind? Or that she returned? They barely spoke for a year; he wanted the escape offered by America so badly that he didn't understand how she could turn her back on it. She'd abandoned him -- and his dream. For Christmas and his birthday, when she presented him with gifts, he'd turned away: "I don't want anything from you."

Now, on the phone, he apologized to his sister. Her love had always mattered. When he was a young boy, he bought a Snickers bar at the shop near their house. He cut the candy into identical pieces for his family.

He wanted all of them to love him the same.

Mark

L. Baer/US PresswireIn the days after Gregory died, his

uniform arrived in Haarlem from Seattle in a UPS box.

Mark

L. Baer/US PresswireIn the days after Gregory died, his

uniform arrived in Haarlem from Seattle in a UPS box.November 17, 2011

Five days before he killed his brother, Jason Halman walked into the Neptunus baseball team's clubhouse in Rotterdam, joining his new teammates for the first and last time. He looked pale. He began yelling incoherently. An old friend looked him in the eyes and they seemed empty. Jason wasn't there.

"What's wrong?" the friend asked someone.

"He doesn't sleep or eat."

Jason paced the small weight room, freshly showered, wearing gym clothes but skipping the workout. His new teammates listened in horror. Many kept their distance. Head coach Jan Collins, who grew up with Eddy in Aruba, heard the noise.

"Not again," he thought.

He called Jason into his small office. If a ballplayer stretched out his arms, he could touch both walls. First Jason sat inside the locker next to Jan's desk, and when Jan asked him what was wrong, Jason leapt up and hugged the coach.

Jan leaned in and smelled for booze.

Clean.

Jason started his rant again. I tell my brother I love him. He won't tell me he loves me back. I'll never do anything to embarrass him. I'm gonna show you.

"I know already."

I should be in America with Greg. I have to be there. I want to play in America. I love Greg. I can't leave him alone there. For a long time, I've been ashamed of my father but not anymore. I'm proud of my father.

Suddenly, Jan was back on a dusty ball field overlooking blue water, 45 years ago. Goats wandered the little patches of grass. Skinny, desperate kids.

I am my father's son, Jason said.

Eddy -- a child, bragging about scouts who'd sign him and take him to America. Eddy -- proud, violent, talented, wounded Eddy. Eddy -- who'd call Jan the day after Jason killed Gregory and talk about himself. "If they had scouts in our days," he would say, "you will make it and I will make it."

"Those days are gone," Jan would reply.

Things buried in the past

Eddy Halman's boyhood home is a rectangle of wood and metal. It grips a square of earth past the top of a hill on the poor side of Aruba. At the crest, you expect a view down into the blue water that surrounds the island, but instead, fields of tall, skinny cacti rise on both sides of the road. Thousands of them, with tight, outstretched fingers. They look like a burned forest. Enormous snakes find shade in the cactus-covered hills. They didn't exist on this island until builders shipped in sand for a new prison. The sand contained eggs.

This is where it began.

"I had to run," Eddy Halman says.

He ran from that house at the intersection of pavement and dirt. His late mother ruled this space, with her stern face and church glasses. She stood tall and thick. Violence and love were the same. She used a belt. If Eddy lost a fight, his mother sent him back out until he won.

Jake Roth/US PresswireGregory Halman (left) talks with left fielder Milton Bradley during a spring training game against the Los Angeles Angels in March 2011.

His father drove a Buick and danced with women on the beach. He visited Eddy a few times. Eddy's mom married a small, meek man, one she used to drag out of bars. They had almost a dozen kids. Only Eddy, the oldest, had a different father. He grew up and played ball. He sneaked drinks from a paper bag behind the dugout. He fought at the first hint that he'd been made a fool. Teammates joked about how often, and with such anger, he said the word "f---."

His chance was baseball.

He grew strong and fast. Huge hands. Wide collars. The Halman smile.

"He looked like Greg," says Tony Rombley, a family friend.

Eddy went down to the beach with his coach, Juan Maduro, on days off. He had a prominent weakness. His aggressiveness infected his game, leaving him on his front foot, off balance, lunging at breaking balls like a man snatching at a fluttering lottery ticket. They'd go down to the flat piece of beach. Juan threw curve after curve. Eddy watched the first few to get the timing and then tried to connect.

"I'm gonna show you," he told his coach.

A scout from the Boston Red Sox wanted the Halman kid and two others to fly to Caracas, Venezuela, for a workout. A real look, which Maduro remembers clearly but Eddy says he doesn't recall. If the Arubians did well enough, they might end up in the States. The Red Sox would pay for the airplane ticket, but the boys needed parental permission. Maduro went to the house where pavement intersects with the dirt.

Eddy's mother refused.

Eddy fell in love with a girl named Joan Hodge. The first time he hit her, she says, was outside the Bonaire Club.

She was 14.

He hit her outside the school.

She says Eddy was standing by the supermarket, across from the one exit, waiting for her classes to finish. Joan walked out with a friend. Her friend ran when Eddy punched Joan in the chest. Joan's mother heard about it later and called the police, so Eddy threw rocks through her windows.

He slipped in through the back door and threatened to kill Joan. He threatened her brothers, who were small and scared. He threatened her father. Eddy got Joan pregnant, and after she gave birth to their daughter, Molly, he hit her outside her home.

The first punch split her lip, blood wetting her chin. The second punch landed in her eye and her head exploded with light. The third punch, to her chest, knocked her down. Then he kicked her. Years later, sitting in the house where he broke out the windows, she flinched at the mention of his name.

All those years ago, the clock ticked on Eddy Halman. The Antillean team flew to Holland for a tournament, and when they gathered at the airport to return home, Eddy Halman never showed. He ran away from the house on the hill. He ran toward the promise of a new life. He met a woman and fell in love. "I'm happy now," he told his uncle. Four children were born in about as many years. The middle two were boys, and they wanted to play baseball like their dad. The oldest son gripped a Louisville Slugger when he was only twice the size of his father's hands. Eddy Halman built his new life, never knowing it was a prison, or that eggs lived in the sand.

November 18, 2011

Three days before he killed his brother, Jason didn't sleep. He sweated through his clothes. Thoughts jumbled. Killers lurked just out of sight, he told his father. They spoke to him. They were inside of him. He wore sunglasses to hide his fear. They could see his fear through his eyes. He asked for music. Music brought him peace. When music played, the voices stopped. Music stopped the killers. He sat in front of the television and watched the new "Planet of the Apes." He wanted friends to watch it with him. Study the green-eyed monkey. The green-eyed monkey isn't afraid. The green-eyed monkey kills the big, black gorilla. The gorilla is dead. Eddy is dead. The green-eyed monkey is free. Jason is free.

Recognizing the darkness

Eddy returned to Aruba a few times, spending Gregory's money. He rented fancy cars. He pissed away cash on booze. His daughter with Joan, Molly, got calls from bartenders to come get him. People laughed behind his back. "You hear what they're saying?" his uncle pleaded. During the worst of it, he wandered the town, looking over his shoulder for people who weren't there. "I've heard voices," he says. "I saw tigers. I saw birds and all kinds of s---."

November 19, 2011

Two days before he killed his brother, Jason Halman rocked through a sleepless night. The shadows closed in. At 3:44 a.m., he posted 2Pac's "Me Against the World" on Facebook. He tapped out a comment: "Only because I wanted to be like my own brother."

For the next 26 minutes, he opened up, a controlled spasm of feeling. He posted a bookend song, one of apology. 2Pac's "Dear Mama." Like the first song, it talked about dark nights and brighter days, and the need to hold on. Fear and hope. The things Jason fought hid inside himself, like snake eggs in sand, waiting to hatch.

November 19, 2007

It happened early one Monday morning. Samuel Baptist, Eddy's half-brother, suspected his wife prostituted herself, that she used cocaine and, to control his mind, secretly drugged him, too. A subsequent psychiatric evaluation of Samuel diagnosed a "serious psychotic illness, in particular a delusional disorder centering on delusions of aggravation and unfaithfulness." The couple stood in their backyard an hour south of Amsterdam. Their two children, 16 and 18, slept upstairs. Samuel confronted her about her secret life. She denied it. He stabbed her in the chest with an 8-inch kitchen knife. She fell to the ground, blood flowing toward her left shoulder. The neighbors heard shouting. Then moaning. His wife lay there for hours before Samuel called the police with an impossible story about self-defense. They found his wife dead. A neighbor said that, through the dark, they thought they saw a person on the ground while another person sat next to them, mumbling reassuring words. The shadow then stood up and walked back into the house.

November 19, 2011

Twenty-four hours before he killed his brother, four years to the day after his uncle killed his aunt, Jason Halman returned to the Internet. In two hours, he posted more than 60 times, one after another, topics changing, coherence wavering. The pain came out first. All he wanted was to quiet the noise.

"I'm trying to sleep. I can't sleep."

He quoted lyrics. He pleaded.

"Did you guys have that much time left? … Wish I could meet Milton Bradley and looked into Griffey's eyes when we talked. … "

His pleas turned aggressive and found focus, aimed directly at an unnamed, invisible nemesis. Anyone up early in the morning on the day before Jason Halman killed his brother watched a battle, one he'd always been destined to fight. Jason started strong.

" … no time to doubt … get off my back … bitch im a boss … come lookin for me im right here bitch … middle of your street so the whole hood will hear this … belly of the beast."

The battle turned. His strength faded.

"When can I get some rest? … Walking around clueless literally … don't get it at all anymore … why it always takes so long for me … what do I miss? … I'm always told I am different. Why?"

He seemed defeated.

"tired … any help? Goin once … somebody stop me … forgive me lord for I shall not want …"

The posts stopped. Four hours later, almost free from a long night's clutch, he sent a text to Landsmark.

"The voices got me tired," he wrote. "They know me. You are who you are boy. You know we're done with this s---."

When Albert looked at Jason's BlackBerry PIN status, which displayed next to his name, he found a strange message: "My heart is a house."

April 29, 2011

Six months before, when Jason still played on the Dutch national team and seemed happy with his life, he went to his new tattoo guy, Azi, for the final session in a dramatic chest piece. They'd worked on it for the past two weeks. The design belonged to Jason, as did the unspoken meaning. His future looked bright as he lay down on the table and put on headphones. Azi's needle-gun buzzed. When it was done, Jason rose and looked in the mirror. There. Just below Feel the Pain: A broken heart, with a skull-handled knife stuck through it, trapped in a yawning black hole, covered by the thick bars of a prison.

November 20, 2011

Fifteen hours before her oldest son died, Hanny slipped out of the boys' apartment and sat in her car. She cradled her telephone and made the call to a doctor. Upstairs, Gregory, Eddy and Eva were watching Jason unravel. Naomi searched for flights home from Italy. Hanny explained everything to the doctor on the phone: The first conversation, the home-cooked dinner, Jim Lefebvre, all of it. The doctor scolded her for being emotional.

"Do you think he is a danger to himself or anyone else?" he asked.

Hanny said she didn't know. She wasn't a doctor. He agreed to send someone over. Three hours passed. Jason showered and dressed. He changed clothes. He changed again. He wanted to walk outside but couldn't find his key. Hanny refused to give him one. She called the doctor back and they promised someone would come. She went into Jason's bedroom upstairs.

"There's a doctor coming," she said.

"I don't need a doctor."

"You are saying things I don't understand."

Around eight, ambulance lights lit the narrow street. Hanny ran downstairs in a panic, worried Jason might see.

"What's going on?" the doctor asked.

Hanny, frustrated, told everything again: the disappointments, the pain. They stood on the staircase, which climbed past the living room up to the third floor, where Jason and Gregory each had a bedroom. They quietly went in to see Jason, stretched out on the bed.

Jason leapt up, cursing, talking fast. Gregory stood in the doorway. The doctor took a step back. Hanny saw fear in her eyes. The doctor said she'd file a report and that the family should call their regular doctor in the morning. Then she fled.

A grain of rice

A specific enzyme, known as GSK3, probably altered Jason's body clock, which is located behind the eyes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, in the hypothalamus. That's one of the reasons people take lithium for bipolar disorder. It regulates the body clock. The circuits of the prefrontal cortex, the brakes for the limbic system, were likely malfunctioning as well. Without the brakes and with a malfunctioning body clock, a series of dominos fall. A state of primitive nature returns. Fight and flight. Nothing separates thought from action. Fear doesn't lessen or go away. Imagine almost being in a car wreck and still feeling the intensity 36 hours later. Delusions begin. Big plans, as well as paranoia that others are attempting to crush your plans. Rapid speech. Disconnected thoughts. Anger. Hearing voices. The dominos fall, click, click, click. Drinking or drugs make the symptoms exponentially worse, as does lack of sleep. These are the signs of the initial manic episode in someone with undiagnosed bipolar disorder. It is hereditary, but there are cases in which one identical twin gets the illness while the other does not. Random, maybe. In almost all cases, the disease is awakened by a trigger. But, scientists say, a manic episode does not have the ability to create new feelings. A person with no history of violence is unlikely to turn violent. Every delusion flows from some seed already planted, like the disease itself. Mania amplifies. The knob gets cranked to 10. The brake wires are cut. The person is out of control. A prescription or even a good night's sleep might slow the mania. The super charismatic nucleus is the size of a grain of rice.

November 21, 2011

About 85 minutes before he killed his brother, Jason Halman slipped out of the house. The previous few hours had been quiet. Jason turned off the music at around one. The Internet posts stopped an hour or so before that. The last dozen made little sense, talk of being born in hell and lazy eyes. There was a moment of clarity: "I will never leave a brother behind again."

Just before four in the morning, after almost four hours of Facebook silence, Jason pulled out his phone and typed a final message:

"Unbroken hearts can't be broken without love but have fun trying."

Jason wandered for about 45 minutes. He didn't bring his key. He arrived at 17A and couldn't get in. Gregory slept upstairs. Less than a half hour before he killed his brother, Jason kicked on the door and shouted for someone to let him inside.

Brothers for life

There is a final thing Jason neglected to tell his roommate three years ago in that Italian hotel: Not everybody failed him. Gregory believed in Jason. So much so that he begged the Mariners to sign him. Asked so many times that the team finally relented, sort of, as a favor to a highly valued prospect. Finally -- best as the team can tell, it was several months before the incident in Italy, although nobody there is sure -- Jason flew to the Mariners' spring training facility in Peoria, Ariz., down the street from a P.F. Chang's. For about a week, the brothers played together, as they'd done in the Griffey poster years before their separation, until the Mariners saw enough of Jason Halman to say no.

Reuters/Mike

CasseseGregory Halman was 24 at the time of his death. His

career batting average was .207, with two home runs and nine RBIs.

Reuters/Mike

CasseseGregory Halman was 24 at the time of his death. His

career batting average was .207, with two home runs and nine RBIs.November 21, 2011

"Open the door!"

The words awoke two neighbors across the street. They looked out their windows to see the young man who lived in 17A kicking the door, shouting, "Now! Now! Now!"

"Open the door!"

Gregory let Jason inside.

The house was still.

Then the music started.

A woman who lives next door heard a loud bass rhythm. Gregory went back down to tell Jason to turn off the stereo. Gregory's former girlfriend, who'd come over to support him, stayed in his room. Jason pulled a butterfly knife, the kind with the blade enclosed in the handle, held shut by a latch.

Gregory put up his left arm to defend himself.

The blade cut the left side of the neck, near the carotid artery. The blood, bright red and rich with oxygen, spurted out of the wound. Doctors call this arterial spray.

The walls were stark white.

Photographs hung on the walls, the brothers as boys, with curly hair and big smiles, when they'd huddled over baseball cards and pictured their own.

Gregory seems to have taken a few steps before collapsing against the wall, opposite the big mirror with the black frame.

Jason ran up the stairs. He was covered in blood.

AP

Photo/Bas CzerwinskiA forensic expert leaves a house where

Gregory Halman was found bleeding from a stab wound in the street in

Rotterdam, Netherlands, on Monday, Nov. 21, 2011.

AP

Photo/Bas CzerwinskiA forensic expert leaves a house where

Gregory Halman was found bleeding from a stab wound in the street in

Rotterdam, Netherlands, on Monday, Nov. 21, 2011.

Love and devotion

Several days later, Hanny arrived at the house with supplies for a final act of motherly protection. It didn't seem right to leave the job to an anonymous Hazmat crew. Her son bled to death on an off-white linoleum floor, and she'd be the one to clean it up.

November 21, 2011

The first ambulance call from the house came at 5:34 a.m. A heavy fog shrouded Rotterdam. The flashing lights popped in the low-hanging clouds. The paramedics rushed toward the house, the police a few minutes behind. Blood flowed like words. When a doctor looked at a picture of the body, he said that an inch in any direction and Gregory would have needed a small bandage. Instead, his own heart killed him, each beat expelling more blood from the wound. The stabbing likely felt like a bad shaving cut. He felt a wetness, like someone had poured a pint glass of warm water on his torso. He would have felt woozy, then severe nausea. His blood pressure would have dropped and the intensity of the spray would have diminished. His vision would have clouded. And then he slipped away, bleeding to death in minutes from a tiny opening six or seven inches from the cross on his back.

November 21, 2011

Minutes after Jason Halman killed his brother, the street glowed blue. It was quiet and cold. No sirens wailed. Jason stood outside the house. Cops shouted to get down. They rushed him. Waking neighbors heard everything.

AP Photo/Bas CzerwinskiDutch police arrested Jason Halman in the stabbing death of his brother.

"I want to see my brother!" Jason yelled. "I want to see my brother."

Police cuffed Jason and got him to the waiting car. He resisted.

"I miss my brother! I miss my brother!"

The words rose out of the fog into the open window of apartment 24B.

"I am alone!" he shouted.

The police car drove away, leaving Gregory inside, taking Jason to a padded room. A family lawyer visited the next day and found Jason naked. The killing lurked in his subconscious, and he'd torn away his clothes, driven by a ghost he couldn't see or name, trying to destroy everything he could touch.

In the end

The Halman brothers haunted their tattoo artist. One day not long after the murder, Ponziani saw a picture of Jason's heart tattoo and felt the bitter sorrow of someone who understands too late. The psychology of tattoos fascinates him. A dragon represents what a man hopes to be. A heart is the most honest, a window into the soul. A broken heart in a cage is a heart that longs to be free. "He was in pain," Ponziani said. "That's a sign of distress." He looked at photos of Jason's tattoos again. Something else became clear. He saw an hourglass he did, and then a tattoo of a watch drawn by someone else. Every tattoo he'd ever done about time meant the same thing: inevitably, inexorably, life was running out. An awful knowledge settled over him. Nothing could have prevented those 17 days in November. We are made and broken before we draw our first breath.

Postscript: On Aug. 16, a Dutch court released Jason Halman, citing his psychosis. Instead of jail, he will get treatment. On Aug. 30, that decision will be made final. Jason owes his freedom to the support of many, especially his mother, who made impassioned pleas on his behalf. Jason is with his family. Gregory is buried in a small grove near the sea, chosen because the plot reminded his family of a baseball diamond. Three tall trees are the bases, and his grave is at home.

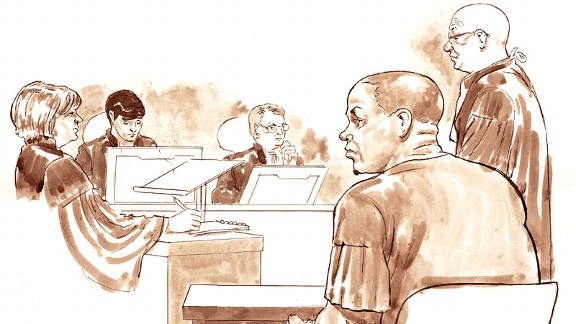

Aloys

Oosterwijk/epa/CorbisJason Halman was found guilty of

manslaughter in the stabbing death of his brother. A Dutch court has

granted him a provisional release from prison pending a final ruling

Aug. 30.

Aloys

Oosterwijk/epa/CorbisJason Halman was found guilty of

manslaughter in the stabbing death of his brother. A Dutch court has

granted him a provisional release from prison pending a final ruling

Aug. 30.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten